Note from the editor: This edition of Forecast was finalised before the tragic assassination of Shinzo Abe, whose remarkable political and economic legacy lies behind many of the positive developments we discuss here.

Between 2012 and 2020, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe introduced a radical reform platform – based on his ‘three arrows’ principles – in a bid to reinvigorate his country’s economy, which had been plagued by decades of deflation and stagnant growth.

The three arrows of his agenda, which became known as ‘Abenomics’, were:

1. Loose monetary policy, including negative base rates and mass bond purchases

2. Robust fiscal policy, which involved stimulus spending, such as on infrastructure projects

3. Structural reform and ‘growth strategy’, such as encouraging more women to work, reforming corporate governance to attract foreign investment and opening up the tourism market

Citywire Selector caught up with three top Japanese equity investment managers to ask whether Abenomics worked, how it benefited investors and whether things have changed since Abe stood down in 2020.

‘Before Abe, politics didn’t matter’

Citywire AAA-rated James Pulsford, who runs the Alma Eikoh Japan L-Cap fund and has more than 25 years’ experience in Japanese markets, said Abenomics was a turning point for the Japanese economy.

‘Almost my whole career it had been a golden rule that politics hardly matters. Before Abe, you had prime ministers who typically lasted a year or 18 months. The Liberal Democratic Party was, by and large, in charge and things didn’t change that much,’ he said.

‘Abe was the first time for a long time when a politician actually made a difference. He had a coherent set of policies and a plan to deal with the persistent deflation, lack of growth and lack of dynamism that had plagued Japan for 20 years.’

Pulsford said Japan very quickly became a much more interesting place for investors, now having its own policy platform rather than ‘drifting on global cycles’ as it had done.

‘The initial rush of Abenomics was the mood change in central bank policy, which produced weakness of the yen but stimulated domestic activity through incredibly low rates,’ he said.

‘The initial market reaction, in the last quarter of 2012, was that a lot of troubled companies performed incredibly well, while the higher quality businesses lagged. Then you got into 2013 and there were very heavy fund plays from foreign investors. Normally, in an average year, you might get a few trillion yen. That year you saw 13 to 14 trillion yen flowing in and foreign investors had an outsized influence on the market.’

‘As Abenomics evolved, it made investing in Japan much more interesting’

James Pulsford, fund manager, Alma Capital

Exciting for investors

Pulsford pointed to the reforms in corporate governance as being key in attracting that extra foreign investment and reinvigorating firms such as electronics giant Hitachi.

‘As Abenomics evolved, it made investing in Japan much more interesting. The improvements in corporate governance and changes in mindset allowed companies to take more dramatic action than what was considered sensible before,’ he said.

‘This included companies like Hitachi, which was a classic old-school, highly diversified conglomerate. It was one of the earliest companies to have a majority of outside directors on its board and they took tough decisions about closing down parts of the businesses. They were not scared to manage their portion of the business portfolio.’

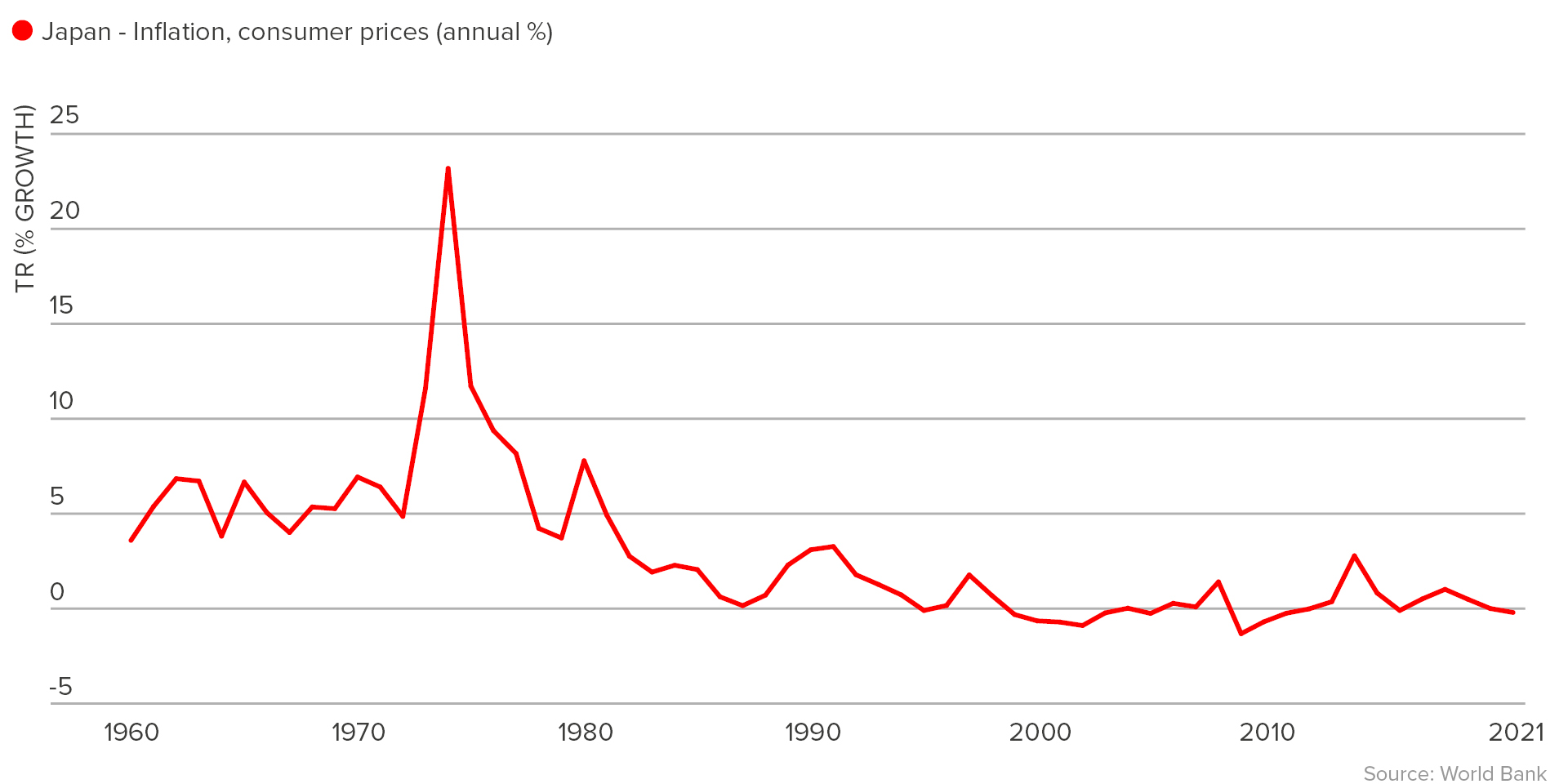

Discussing the loose monetary policy, Pulsford said that increased inflation levels created a ‘much more fertile environment’ for Japanese businesses, which had long been afraid to raise prices, while the structural reform of opening the tourism market boosted domestic demand.

Post-Abe

Since Abe stepped down in 2020, Japan has had two prime ministers – Yoshihide Suga and Fumio Kishida – but Pulsford maintained that there was ‘not much threat’ of a reversal of Abenomics as it was now broadly accepted by the Japanese political class, including the dominant Liberal Democratic Party.

He voiced concerns, however, that the days of loose monetary policy in Japan may soon end due to inflationary pressures.

‘Japan is at a very interesting inflection point. Inflation is still incredibly low compared to elsewhere but it tends to lag in Japan and what’s waiting further down the line? With Japanese policies so opposite to everyone else’s, it has created a huge potential interest rate differential and we can see that in the currency weakening,’ he said.

‘That’s the pressure point for Japan as this is going to potentially make inflationary pressures as they come through even worse. We’re at a very difficult time for Japan.’

‘It was unprecedented and unorthodox monetary policies that they were using and I would argue that it broadly did a good job’

Mayur Nallamala, fund manager, RBC GAM

The right direction

Citywire A-rated Mayur Nallamala, who runs several Asian equity funds for RBC GAM, said the three arrows were a well targeted attempt to address the setbacks Japan had suffered since its stellar economic performance in the 1980s.

‘What Abe was trying to achieve, from greater female participation in the labour market and trying to get that inflation number up, were all logical things to try and revive the Japanese market,’ he said.

‘This was in tandem with other good things happening, like a focus on ESG and corporate governance. All of these things are positive. They never moved as fast as we would have liked, but they never do.’

Nallamala questioned the overarching impact of Abenomics but said it was a move in the right direction.

‘They never hit a lot of their targets, such as on inflation, but at least inflation moved into positive territory in general. It was unprecedented and unorthodox monetary policies that they were using and I would argue that it broadly did a good job. But there are always going to be people who said it didn’t go far enough to work.’

Inflation stations: consumer prices have slumped since the 1970s

Innovation thrived

In terms of investment opportunities during the period, Nallamala pointed to innovative companies that benefited from the increased money supply.

‘They have these periods of time in Japan, where mid- and small-cap companies do well and innovative companies are rewarded a lot. There was a lot of dynamism in share prices. We were interested in new biotechnology companies. High precision technology companies that came in also did very well. A lot of the drivers tended to be quite cool, interesting companies,’ he said.

‘A sceptic would say the Bank of Japan was printing money and buying the share market itself. That’s definitely true but there was a lot of alpha available in the smaller mid-cap segment that’s died more recently. Now you’re seeing leadership change more to large caps which are doing exports.’

Nallaballa echoed Pulsford’s concerns that the yen was now becoming too weak but said it would benefit the export sector.

‘It’s got positives for the export part of the Japanese economy, which is competing against China and Korea, principally. But the concern is imports will become more expensive, especially because Japan is a large energy importer,’ he said.

Mixed results

Citywire AAA-rated Yutaka Uda, who runs the Nippon Growth fund at Eric Sturdza Investments and has a 21.3% return over the last year, had different views on the success of each of the three arrows.

He said the monetary policy arrow, driven by the appointment of Haruhiko Kuroda as governor of the Bank of Japan in April 2013, was ‘very successful’ with the yen weakening as desired and the stock market booming.

‘They purchased huge amounts of Japanese government bonds together with ETFs and Japanese Reits. The policy was very successful with the yen to US dollar rate weakening sharply from 76 in early 2012 to 124 in mid-2015. Stock markets were very strong with the Topix increasing from 859 at the end of 2012 to 1,817 at the end of 2017,’ he said.

But Uda said the fiscal policy was ‘ambiguous’ and not enough was done in terms of the structural reform.

‘Fiscal policy was not good enough. Public works spending was fairly positive in 2013 with 10% up year-on-year, however, it became stagnant between 2014 to 2018 with flat to minus growth,’ he said.

‘The growth strategy didn’t progress much, with the exception of tourism. Inbound tourists to Japan dramatically increased from 8 million in 2012 to over 30 million in 2019. Summarising Abenomics, stock markets were strong with aggressive monetary easing but the economy remained stagnant with its growth only 0.5 % per annum and consumer price inflation less than 1% per annum.’

Uda said that the best five sectors in the Topix to invest in during the Abe tenure were manufacturing, precision instruments, communications, services and electricals.

‘In general, IT and high-tech stocks showed better performance as the Japanese markets were influenced by strong US markets,’ he said.

‘Public works spending was fairly positive in 2013 with 10% up year-on-year, however, it became stagnant between 2014 to 2018 with flat to minus growth’

Yutaka Uda, fund manager, Eric Sturdza Investments

The impact of inflation

Uda said Japan would be affected by the inflation caused by Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but his country, which is more accustomed to deflation, was well placed to deal with these pressures.

‘Relatively, Japan is in a good position to be resilient against inflation and has been waiting for a very long time [for inflation]. We think that beneficiaries of increasing infrastructure investment and higher interest rates with cheap valuations should lead the rally,’ he said.

The Tale of the Three Arrows

Abe’s three arrows was a reference to the following Japanese legend.

A lord handed each of his three sons an arrow and asked them to break them. Each did so with ease.

He then produced three more arrows bound together and asked them to snap them and they couldn’t.

The moral was three pillars are much stronger than one.